Surface Tension

- Shannon Devy

- Jul 7, 2025

- 6 min read

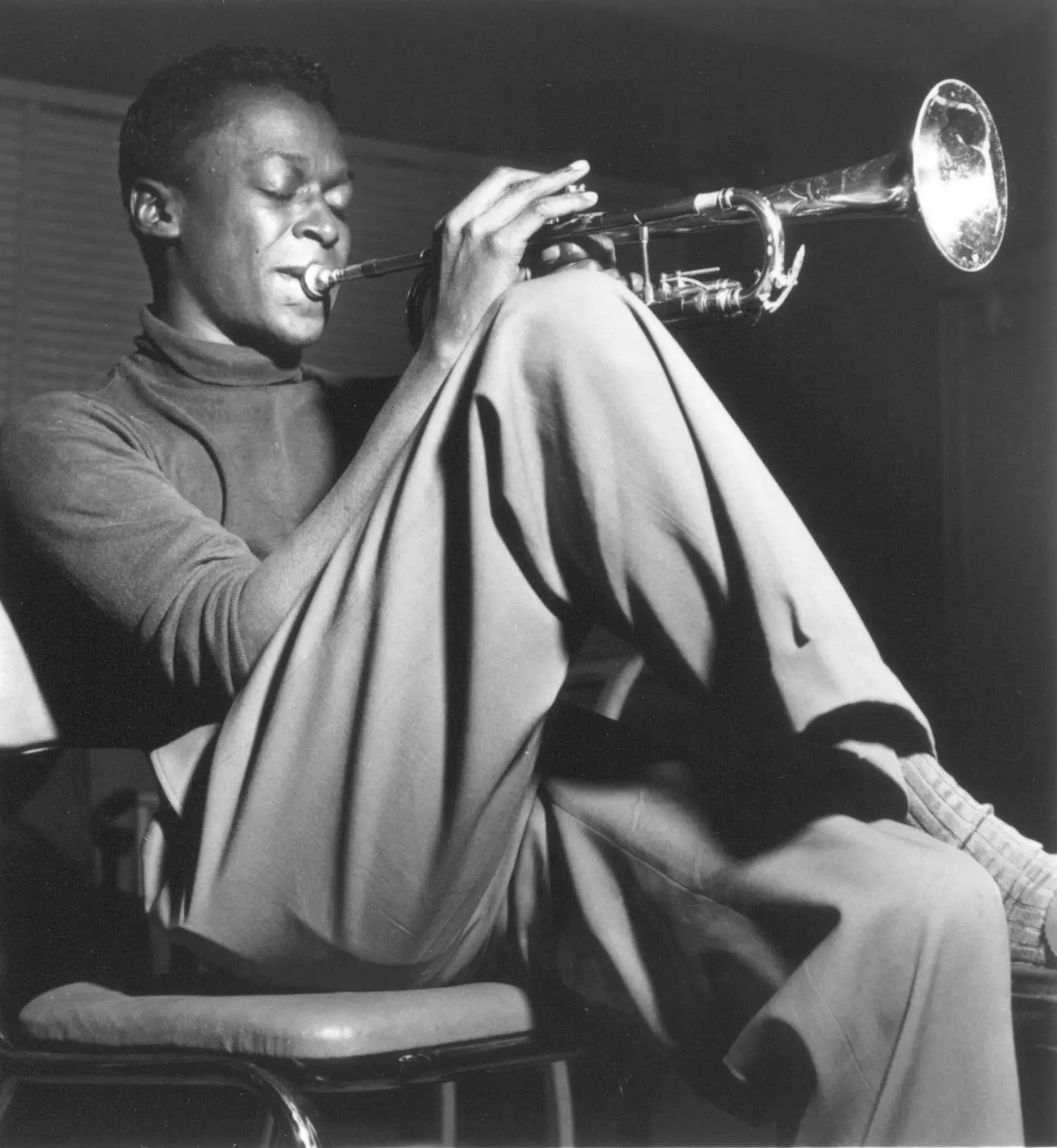

Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue and the strange qualities of jazz improvisation.

On the second day of March 1959, “So What”, the opening track on Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, happened. I say it “happened” rather than “it was recorded” or “it was written” because as Bill Evans raised his hands to the keys to press out the first chord, it did not yet exist.

The next nine minutes and four seconds, faithfully snatched out of the air in the main room of Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studios, would go on to signal a modulation in the jazz genre. Miles said modal, and so it would be. Kind of Blue ushered in a new era. Not that Miles cared – by the time the world caught up (and it didn’t take long), Miles had moved on to something new, as usual. Regardless, Kind of Blue would go on to become the best-selling jazz record of all time – “So What”, another seminal standard fallen out of Miles’ pocket. He never went back to get it.

In the breadth of the jazz canon, Kind of Blue is an album that approaches perfection – a holy artefact, fittingly recorded in a converted church, which has collected millions of acolytes in the years since it was released, all more than willing to keep it alive by sounding it again and again. Hugh Masekela called Kind of Blue Davis’ “lasting and greatest revelation”, and I think this describes it perfectly. How can we account for the fact that some creative outputs feel like they have been revealed or disclosed, rather than written or composed? What I am interested in thinking about here is why some creative practices and works, jazz improvisation in particular, feel miraculous. “So What” is, for me, undeniably one of them. What can it tell us about what it means to create?

The night my father died, I bought limited edition blue vinyl pressing of Kind of Blue at Tower Records in Shibuya, Tokyo. I had been looking for a copy for years, but in all my crate digging, I had yet to come across one. At one record fair, I entered into a hushed negotiation with a dealer who said he had a friend with a near-mint first pressing he may be persuaded to part with. The conversation had the quality of a drug deal. I took his number, but he never returned my calls. I carefully carried the record by hand from Tokyo, to Addis, to Cape Town. I played it in the dark and disappeared.

My copy of Kind of Blue includes the original liner notes, written by Bill Evans. They are thoughtful and carefully crafted, much like Evans’ playing. Titled “Improvisation in Jazz”, the notes begin with a description of a Japanese visual art in which the artist uses specific materials – thin parchment and black water ink – which make the interruption, erasure or correction of any brush stroke impossible. Practitioners must work smoothly, deliberately, and confidently, otherwise they risk the destruction of the parchment itself. “These artists,” he writes, “must practice a particular discipline, that of allowing the idea to express itself in communication with their hands in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere.” This, he seems to suggest, is the essence of jazz improvisation, a mode of creation located beyond the mechanism of conscious thought: a pure state of flow, idea to execution, via the muscle, bone and sinews of the hands.

“The resulting pictures,” he continues, may lack the composition and textures of ordinary paintings, but it is said that those who see well find something captured that escapes explanation. This conviction that direct deed is the most meaningful reflection, I believe, has prompted the evolution of the extremely severe and unique disciplines of the jazz or improvising musician.

What we are hearing when we listen to jazz improvisation is a creative act unmediated by fear or logic – the purity of instinct rendered in the medium of sound. “You will hear something close to pure spontaneity in these performances,” writes Evans. What infuses jazz improvisation with its particular, almost magical, quality is that it gives us access to the exact moment of creation, at the very instant the creative act enters the world. We feel the shimmering surface tension between what isn’t and what is.

Recorded music has singular, peculiar qualities. My copy of Kind of Blue sits mute on my desk, but “So What” waits within it. I know it to be located there. Under the right conditions (under the drag of a stylus) I am gifted nine perfect, perfectly preserved minutes, just as they occurred. Nine minutes, 62 years old. Does it exist when it is not being played?

In Musicophilia, Oliver Sacks’ exceptional exploration of music and the brain, Sacks describes something astonishing that happens when we play or listen to music together: In all societies, a primary function of music is collective and communal, to bring and bind people together…(when) music is a communal experience, there seems to be, in some sense, an actual binding or “marriage” of nervous systems.

This binding process is called “neurogamy”. He goes on:

The binding is accomplished by rhythm – not only heard but internalised, identically, in all who are present. Rhythm…synchronises the brains and minds of all who participate.

To bind one’s nervous system to another, to synchronise brains and minds – what a profound act of intimacy. Can we get any closer to one another than that?

When we listen to jazz musicians improvising together, we are overhearing a conversation, carried out in a deep language which each player has mastered and delivers in their own unique dialect. Chick Corea said, “It’s one thing to just play a tune, or play a program of music, but it’s another thing to practically create a new language of music, which is what Kind of Blue did.”

On the morning of what would become the “So What” session, Evans met Davis at his apartment to sketch frameworks for each tune, jotting down a few handwritten notes on scraps of manuscript paper outlining melody lines and modes to use. Fred Plaut, engineer and avid photographer, took photographs of the second of the Kind of Blue sessions, including a picture of Adderley’s music stand, which held a few scale outlines on one of these scraps of manuscript paper, written by Evans. Across the top corner, Evans had written “Play in the sound of the scale.” No further instructions. No further preparation at all was made for the session, and each track on Kind of Blue is a first full take.

Fluidity and fluency. There’s an alchemical inevitability to Kind of Blue, a sense that, as one critic put it, “it all had to happen exactly as it did”. But mastery creates the illusion of ease. From the point of view of the musicians present that day, this session which changed music was almost pedestrian. Recalling that morning, Jimmy Cobb said,

I remember getting up in the morning – kind of excited, because I knew I had a record date with Miles Davis – putting on my clothes and getting my instrument together. I went to Columbia’s 20th Street Studio, took my drums inside and set them up, and waited for the guys to trickle in and see what we were going to do.

On the session, Evans said, Professionals have to go in at 10 o’clock on a Wednesday and make a record and hope to catch a really good day. The rest of it is being professional, reaching a high degree of performance in the area that you’re trying to work.

When asked about Kind of Blue in a 1986 interview, Davis said, “…the right hour, the right day, and it happened.” Simple as that. Was it as simple as that? Of course not. To close that gap between the thought and the hand, impulse and articulation – to remove the “deliberation” from the creative utterance – that takes decades of work. When that circuit is clear and closed, (and anyone who has seen a jazz pianist sing an improvised solo while simultaneously playing it will know what I mean), it looks, sounds and feels a hell of a lot like magic.

We’re lucky we caught it.

Comments