THE RASTAFARI MESSIAH & THE HONKY TONK NUN

- Life & Style

- May 9, 2024

- 2 min read

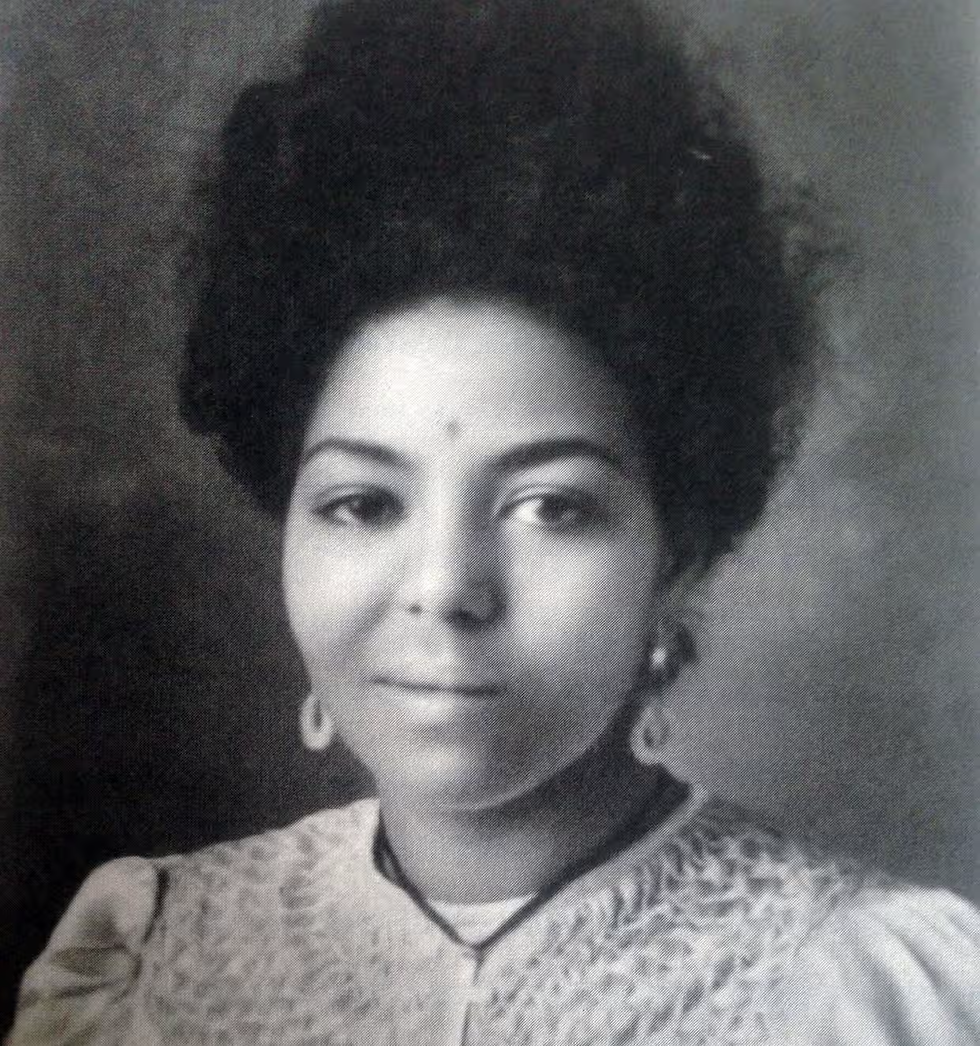

The Ethereal Music of Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou

By Mia McCarthy

IN THE 1930s, an exceptionally talented Ethiopian pianist named Yewubdar Guèbrou became the civil servant and singer of Emperor Haile Selassie. Incidentally, the Emperor is believed by some followers of the Rastafari movement to be the returned messiah, destined to lead the peoples of Africa and the African diaspora to freedom. In life, the Emperor politely denied these assertions of his divinity.

Messiah or not, the celebrated Emperor attracted the servitude of Guèbrou, who herself would come to dedicate her life to twin spiritual pursuits: a relationship with God, which would earn her the honorific “Emahoy”, and a relationship with music, which would earn her the BBC-bestowed nickname “the Honky Tonk Nun”.

In early childhood, Yewubdar and her sister, Senedu, were sent to boarding school in Switzerland, where Yewubdar studied violin and piano. She returned to Ethiopia to continue her musical studies, but Mussolini had other plans. In 1937, Yewubdar and her family were taken prisoners of war during Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia and deported to islands near Sardinia. Some time after the war, while she was working for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs under the appointment of Emperor Selassie, Yewubdar was offered the opportunity to study at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Although an illustrious career as a concert pianist seemed certain, the prospect fell through for reasons that Emahoy never disclosed.

The outcome would have a profound impact on her life. Yewubdar secretly fled Addis Ababa to become a nun, took on the religious name Tsegué- Maryam, and spent the next decade of her life in a hilltop monastery in the Wollo region. “No shoes, no music,” Guèbrou told BBC journalist Kate Molleson. “Just prayer.”

Guèbrou maintained a monastic life for decades but, eventually, she found her way back to music. She relocated to a Jerusalem convent in the 1980s where, in austere quarters that housed little more than a bed, she resumed composing and practising music. Although Emperor Selassie had helped Guèbrou release her first record in Germany in 1967, it wasn’t until 2006 that she achieved widespread recognition. A compilation of her piano compositions were issued on the Éthiopiques record to critical acclaim. Writing for Pitchfork in 2020, Alex Westfall described her music as “the sonic equivalent to infinity — untethered by conventional meter or rhythm, as if Guèbrou’s instrument holds more keys than it should.”

Indeed, Guèbrou’s fingers were as fluid as water on the keys. Once, as a schoolgirl in Switzerland, she was asked by passers-by what she was playing on the piano. “The storm,” she answered, simply.

Perhaps her gently tempestuous style was informed by the passage to Europe, which she described as such: “There was only heaven and sea for one month.” More broadly speaking, her musical journey reflects the riverine progression of her remarkable life. Musical prodigy, Emperor’s favourite, prisoner of war, servant of God: Guébrou’s capacity for transformation was akin to water itself.

Guèbrou died last March, aged 99. During her life, she composed over 150 songs for piano, organ, opera, and chamber ensembles, compositions which she stored in crumpled Air Ethiopia bags. Her contributions to music are a poignant reminder of how the richest of lives spring from humble beginnings.

Comments