CRAFT

- Shannon Devy

- Nov 26, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2025

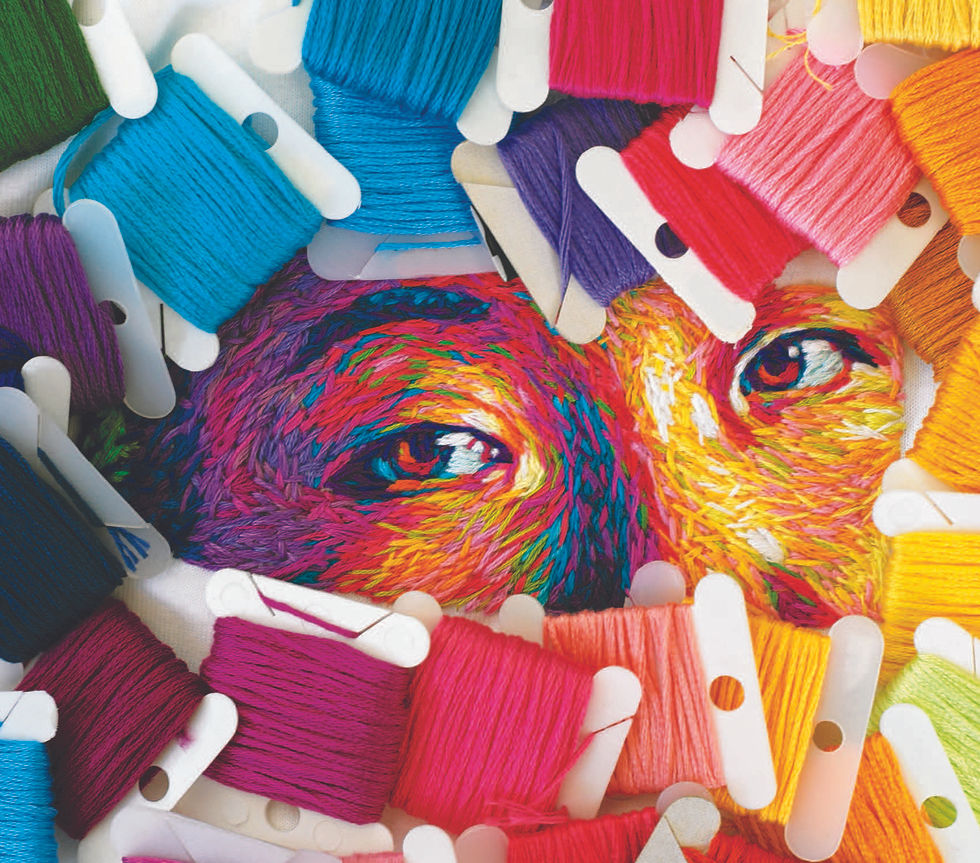

AN INTERVIEW WITH EMBROIDERY ARTIST DANIELLE CLOUGH

Danielle Clough has given up her iPhone. Well, sort of. “I’ve noticed that my attention is very fractured because of my phone, so I got a light phone a few months ago, and I am loving it,” she says. We’re about halfway through our mid-August Zoom interview, and we’ve reached the crux of the matter. Danielle – gracious, open and generous with her time – is dialing in from Paradigm gallery in Philadelphia, where she’d just set up her latest headlining exhibition, Crewel Intentions. She tells me this is the first body of work that she’s made that she feels has real consistency – something she attributes in large part to her light phone. Without constant digital distractions, she’s able to focus, and by getting as far away from digital stimulation as she can in the studio, she’s created the conditions for boredom to happen without the “convenient boredom buster” of her phone. It’s within that boredom, and the tinkering and play that cures it, that the work unfolds.

Words: Shannon Devy

Or rather, unspools. Clough is an embroidery artist, after all, although she’d more readily refer to herself as a crafter. Hers is a tactile, ancient craft with a timeless and enduring universal appeal – one that has experienced a surge in popularity of late. In inner city craft clubs, living rooms, bedrooms and internet forums around the world, hundreds of thousands of people are rediscovering needlework, perhaps as some kind of antidote to modern living. It makes sense. Quiet, tactile handwork exists in direct opposition to the abstract, nightmarish and relentless barrage of the endless scroll. I can’t think of anything more antithetical to an AI output than a piece of handworked embroidery. In the attention economy, choosing to invest your deep attention into something you can hold in your hands seems like resistance, or revolution.

There’s an element of survival to it, too. “I’m seeing it more and more – how many people want to be in workshops,” says Clough, “We have so much digital stimulation, to actually use your hands, to sit with people, to enter a community, is just absolutely amazing.” It’s also about doing something for the sake of doing alone in a society that is preoccupied with outcomes and achievements. “Craft has such an easy point of access,” says Clough, “and you’re able to do it without feeling like you have to be good… it really helps you bypass your critical voice, because the joy is in the making, it’s not in the outcome. So much of our life is about, How do you turn this into your job? Who’s going to buy it? How many likes did you get? What’s it worth?” Crafting, for the average crafter anyway, gives us a rare opportunity to step out of the modern value system and to do something for the simple joy of it.

It’s a profound relief.

Clough is, of course, not your average crafter. She is an acclaimed professional artist who has managed to achieve what most people only dream of achieving – a livelihood generated from art. While her workshops and teaching help facilitate an escape from a value-based approach to crafting for others, it’s not an approach she can easily escape herself. I ask her about the tangled and paradoxical relationship between creativity and business that confronts the working artist:

“It’s definitely something that I have to consider,” she says. “I live off art.I come from quite a commercial background, and because of my advertising background, I still don’t really consider myself an artist. I consider myself a crafter.

I try to treat my practice as if my work is a product. It’s not necessarily about how I value my work, but rather about how I build systems around it. What do I create? How do I create it in the best way? What’s the best way to release it?” Business person, entrepreneur, administrative wiz, and social media savant – the skillsets involved in running a successful artistic practice are varied and extensive. Clough appears to take it all in stride, but she’s clear that there’s no one right way to do it. “It’s important to build a commercially viable practice around the work, and loving the work in the way that you want to love it and work it.”

What’s more, commercial success doesn’t have to come at the cost of artistic integrity and inspiration. “Because I come from an advertising background, I know how to take on a commercial project and not feel like it’s affecting my artistic integrity,” she says. “I’m very protective about doing work that I love – I won’t take on just any job, because I think it's super important to protect your process and to protect what you love. If I’m approached by a company and I’m like, Wow, that’s exciting, that’s going to challenge me, that’s going to pay my rent. Tick, tick, tick! – I use that as a gauge.” With commercial work keeping the lights on, there’s more time to focus on the rest of it.

You can trace the thread of Clough’s latest exhibition, Crewel Intentions, all the way backto a second-hand sale in Australia, where she picked up her first vintage Playboy magazine (“I was like, these are amazing!”). Years later, she found another stack of old Playboys in a second-hand store in Fish Hoek, just across the road from her studio. Mostly from the 70s, they’re missives from another era – thick publications, printed on matte paper stock, full of vaseline-lensed glamour shots and outrageous cigarette advertising.

They’re also an incredible repository of vintage advertising film photography, and it’s these captured moments that Clough extracts and pulls across the decades, recolouring, reimagining and recreating them to make something completely different – something seen as contemporary. In this way, Clough is playing with time, and she’s doing so in an ancient medium. It’s no surprise that themes of ageing and temporality are surfaced through her work. “I think a lot about time…ageing, ageing mediums, ageing people, my own ageing – these women and men that I’m embroidering. Where are they today?” she wonders. In their glamour shots, her subjects are immortalised at the height of their youth and beauty. Today, they’d be old. One can even imagine them bent over their own needlework somewhere.

I first encountered Clough’s work at a gallery in the Silo District in Cape Town, where she was exhibiting as a member of CODA Collective, a group of friends/artists’ collective comprised of Clough, Cynthia Edwards, Olivié Keck, and Andrew Surtherland. I ask Clough about the role of community in her work. She says that, while in the South African context there may be a bit of a scarcity mindset, once you realise there’s an abundance of opportunity and growth to go around, you can start building something together. “There is something magic that can be built up through community, through creating, through collaborating,” she says. “It makes a huge difference. It’s so important for the work itself, but also for making things a little less lonely in what is essentially a completely solo pursuit, sitting with your art.” But it’s a fine balance for an artist as personable as Clough – a little too much community can have the opposite effect. She had to forego moving into a bustling studio in Muizenberg to preserve her productivity. “It was a beautiful building with other creatives. I was like, I really want to move in there, but I know I’m going to be distracted,” she says. “I know I'm going to be the mayor of Harvest Cafe, and I’m never going to get anything done. Being a little bit isolated helps.”

But her actual productive output represents only a fraction of Clough’s professional tapestry. She is actively engaged in building the craft community, teaching all over the world, giving workshops from Australia to Canada, the US to Kuwait, on everything from beginner stitching to more advanced multi-day abstract experimental sessions. She has a fantastic array of online courses available on her website, too – all designed to meet the ever-growing demand for needlework as a craft.

It’s a demand that marks a sort of full-circle return: In the 18th century, embroidery was one of the most highly paid professions. With the industrialisation of the needle, the value of that specialisation was wiped out almost overnight with the arrival of machines that could achieve the same, or superior, results faster, better and cheaper than their human counterparts.

We’ve arrived at a similar moment, as AI’s emergence presents an existential threat to many artistic crafts, opening up important conversations about the value of creative work, the future of the arts, and, quite frankly, our ability to know and trust what is fundamentally real about the world.

Clough’s work feels like a balm in this context, standing as an example of a medium that has survived time, automation, and catastrophic change, and emerged more vibrant, more inspired, and more alive than ever.

DANIELLE CLOUGH

@fiance_knowles

Comments