The Woman & the Wheel

- Life & Style

- Nov 26, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2025

The spindle, whorl & wheel are tools, cognitive artifacts and archetypes that have come to create the modern human mind. For tools are creators of worlds. This month I'm going to spin a real ramble of a yarn. It seems fitting—I've always been drawn to cloth, to the art of textiles. I come from a long line of people with all kinds of sensory sensitivities, and as such was raised to appreciate the weave, quality and the breathability of a fibre. I also come from a long line of men obsessed with tools, so I'm also going to ramble about tools, too. Namely, a revolutionary one (so revolutionary in fact that the word revolutionary would not exist without it).

Words: Tara Boraine

The First Revolution

When we imagine the first wheel, the mind often leaps to transport—chariots, carts, locomotives. (Mine does, at least; I have trains in the blood.) Station masters, engineers… my father grew up on the railroad before running away to study art. Even he, for all his rejection of heritage, loved a good tool. From stone implements found in the veld to Voortrekker wagon wheels, all found their way into his sculptures, oils, and etchings.

The wheel's great leap wasn't originally for transport.

Let's take a leap back to around 20,000 BCE. Here, we find the earliest rotational devices that massively pre-date those wheels we used for transport or pottery. These are called spindle whorls. A spindle whorl is a weighted disc, originally of clay, bone, or wood, used in hand spinning to add momentum and stability to a drop spindle. Essentially a miniature flywheel, its mass and balance help the human maintain rotational inertia, allowing for longer, smoother spinning. Much like a gyroscope, it keeps the spindle steady as it twirls.

For all intents and purposes, a whorl is a wheel—storing and transferring energy through rotation.

Fast forward to Mesopotamia, around 3500 BCE, and women were pottering about. And by pottering, I mean the business of making clay pots. One day, someone (and I'll presume a woman, for story's sake) came up with the bright idea of creating a horizontal spinning platform with which to turn the clay. And thus the potter's wheel was born.

The Cyborg Spinster

Although the term spinster has been a euphemism for "unmarried older woman" since the 1600s, it originally meant "woman who spins." Spinsters are deeply embodied beings, their agency and identity emerging through an intimate coupling with tools—tools that extend, enhance and fundamentally alter not just human capability, but human cognition.

This is what philosophers call "embodied cognition"—the radical idea that our minds don't stop at our skulls but extend into the tools we use. The spindle doesn't just make thread; it shapes how we think, creating rhythmic, recursive patterns in our consciousness.

The case is similar to that of playing a musical instrument. When these interfaces are truly mastered, we see boundaries dissolve. Where does the spinner's hand end and spindle begin? And who is really spinning—the human? The tool? Something novel emerges—not quite human, not quite machine. After all, the spinner only exists in relationship with her technology. Thus concludes my eccentric-sounding theory: Spinsters have been cyborgs for millennia!

The Social Network

Spinning has always been a profoundly social technology. With it, women created parallel social structures where they could increase their human agency. For the spindle afforded them the time and space to exercise leadership, make decisions, share knowledge and build relationships outside the male-dominated mainstream. These spinning circles were tightly connected local groups with occasional long-range connections through traveling spinsters, creating efficient pathways for information to spread across vast distances. Like messages zipping through the internet, these networks made collective intelligence possible.

Spinning was one of the most constant tasks in pre-industrial societies, so women often combined it with other activities. Spinning was portable, so women could work while minding infants or toddlers. One could tend to a slow-cooking stew or baking bread between turns of the spindle. The spinsters' corner was a place for teaching and mentoring—passing down skills, teaching mathematics of measurement, and sharing language.

And where women spun yarns, they would also weave myths, passing down stories, genealogies, and cautionary tales. In Ancient Greece, the Fates themselves lay in women's hands: Clotho, the spinner, spinning the thread of life. Lachesis, the measurer, observing how long a life may be. And Atropos, the thread-cutter, the architect of all endings. News exchange was central to spinning circles, often with the purpose of organizing. Far from frivolous, community gossip formed a vital part of creating a safe and thriving community—after all, it was of evolutionary benefit to know who's who in the zoo.

From Thread to Code

Artificial intelligence too, would have been impossible without a good yarn. From spinning came weaving, the loom transforming single threads into patterned cloth. The warp and weft of fabric? That's binary code.

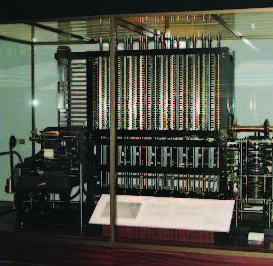

This wasn't lost on Ada Lovelace, the world's first programmer, who grew up surrounded by the Jacquard looms of industrial England. These looms used punched cards to control complex weaving patterns—a direct inspiration for her work spinning the first algorithm for Babbage's famed Analytical Engine.

The Analytical Engine was a ground-breaking early mechanical computer concept featuring the 'Mill' (its CPU for arithmetic and logic, named after textile mills where raw fiber became thread), the 'Store' (memory holding data like warp threads awaiting the weft). It borrowed its entire control system from the loom—transforming the over/under wisdom of warp and weft into the ones and zeros that would become computing's mother tongue. Ada saw what many missed: that these machines could manipulate not just thread but symbols, numbers, even music. The connection between textile and technology runs deep in our collective human history, from spindles to software.

The Universal Interface

The more I think about the wheel, the more it appears to be a rather universal interface. Mechanical, symbolic, cosmic, domestic and ritual, the Wheel encodes circular motion as a generator of change. Across time and cultures there's a notion of a cyclical turning of fate. Dharmachakra. The Wheel of Fortune. Bhavacakra. The Norns. Yin-Yang. Mandala. Rota fortunae. The Virgin Mary spinning in Annunciation scenes… the list goes on and on.

We even have whorls here at home, in our backyard. At Mapungubwe, that golden kingdom on the Limpopo, archaeologists have uncovered ceramic whorls dating back a thousand years. Throughout the Iron Age sites of the highveld and the coastal settlements of KwaZulu-Natal, these small weighted discs appear like breadcrumbs through time, marking trade routes and marriage alliances, technological exchange and cultural fusion.

But to take it way back, to the downright mystical, before any overt evidence of human spinning, we see early motifs of threads. In San rock art, ancient paintings depict "threads of light," and "ropes of god"—luminous cosmic strands that San shamans travelled along during trances. The threads map webs connecting human, animal, and spirit worlds, reminding us that long before wheels or whorls did turn, humans were already spinning, of sorts.

Revolution

What is spin, if not revolutionary? From the twisting of fibers to the fundamental physics of elementary particles, to the spiral formation of galaxies, to the twirling of a dancing girl. From spindle whorls to hard drives to hard-won freedom, revolution follows the same ancient algorithm: tension, twist, release. I doubt it was a quest for ever-increasing productivity that led women to make wheels. If they were anything like the women I know and love, it was probably a deep desire to take more naps. Take more naps, indulge in more pleasure, make more art, and spend more quality time with friends and family. After all, most self-inspired inventions come from humans wanting to do less labour, not more. (Perhaps, as the age of AI automation fast approaches, this notion deserves a bit of a revisit.)

It's National Women's Day, as I finish writing this. It feels significant to be talking about revolution. I think of those 20,000 women marching to Pretoria's Union Buildings, doing their bit to unspool the old order in the name of human dignity and freedom. The whorl, the world, the wheel, spins on. There is much we cannot control. There are many wounds to tend to, much healing to still be done. May our revolutions too, like those brave-hearted women before us, be ones of vigil and song.

I'll leave you with a poem about wheels and tools:

Spindle, quern

Thread & flour

Seasoned Time

And frequent hour

Clothe, nurture

Turn & bake

Buns in ovens

Threaded Fates

Mechatronic

Axle, rim

In a fight

And on a whim

Fueled by pure

Adrenalin

The consequence

Is wearing thin

Fate and dharma

Loops & gyres

Seeds were sprung

In funeral pyres

Axis mundi

Long forgot

Systems stale

The flowers rot

Iron rusts and

Gears grow still

But the ancient

Turning will

Call us home

To what we knew

Before the hammer

Split in two

Roots in earth

Arms in sky

The wheel it turns

We live, we die

We live again

Eternal spin

And at the ending

We begin

Comments